My thesis, currently under the working title “Binaries, Images, & Symbols: The Other in Their Eyes Were Watching God,” aims to examine the depiction of Janie, the story’s heroine, as an (gendered) Other in her own narrative and to filter a scholarly understanding of the way Zora Neale Hurston authored Janie as an Other through the use binary images and symbols in Hurston’s text. I also propose to contextualise the novel, and Janie’s Otherness, in reference to Hurston’s own life experiences.

Chapter One, page one, in my own copy of Their Eyes Were Watching God

For my thesis, my main text is Hurston’s novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937). However, I also intend to look at other Hurston writings, specifically at her folklore collection Mules And Men (1935) and her autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road (1942). I find her folklore collection useful to my thesis in that it also depicts certain animal images found in Their Eyes Were Watching God. Hurston’s biography will be a practical source in order to glean details of her personal life from Hurston’s own point of view.

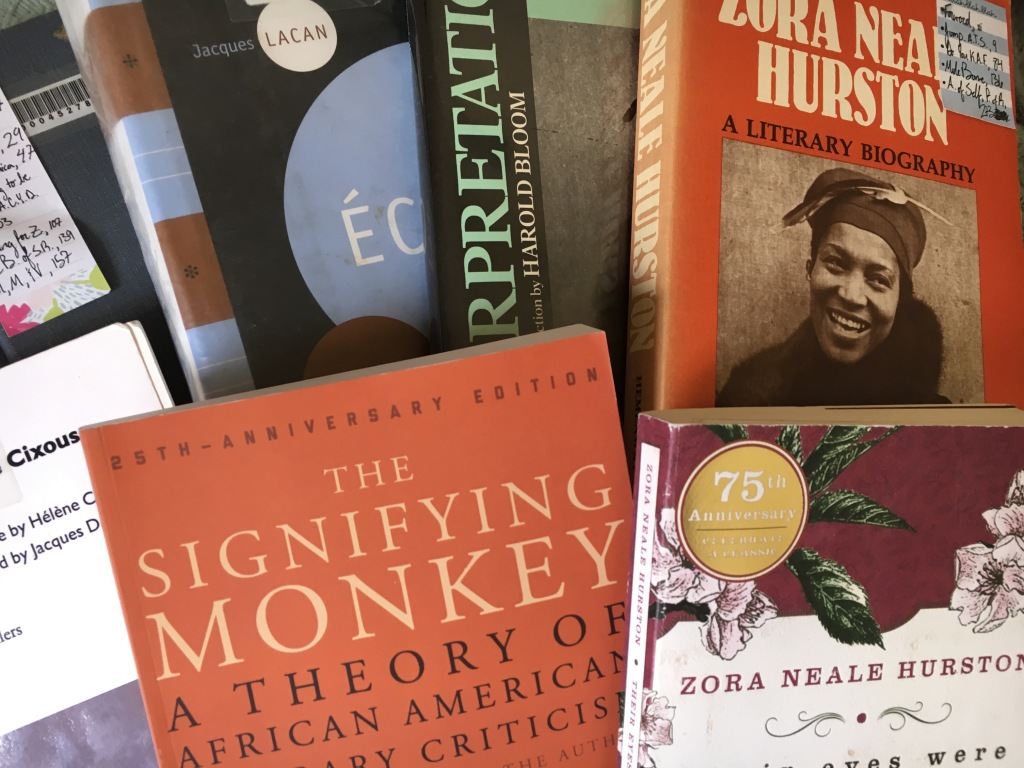

I will rely heavily on two collections of critical essays by Harold Bloom, both his Modern Critical Views: Zora Neale Hurston (1986) and also, Modern Critical Interpretations: Zora Neale Hurston’s ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God’ (1987). I will use several essays out of these collections, which look at a wide range of images, interpretations, and stigmas and terms attached to Hurston’s work overall. Of particular interest to me are essays that look at images/symbols in Their Eyes Were Watching God and/or look binary ideas contained in the novel, such as ideas of sexism and sexuality or communal spaces and private spaces which are addressed in Missy Dehn Kubitschek’s essay”‘Tuh de Horizon and Back’: The Female Quest in Their Eyes Were Watching God“–an essay in Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations: Zora Neale Hurston’s ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God’. As another example of the types of work in these collections, Roger Rosenblatt’s essay in Modern Critical Views: Zora Neale Hurston, titled simply “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” looks at the Other to Self journey for Janie in the novel. At one point he says “she begins as a minor character in her own life story” (29). I’m extremely excited about this essay in particular, as the marginalisation of Janie as an Other in the novel will be part of my thesis. While most of these essays topically address Their Eyes Were Watching God, others address some of her lesser known works–such as, her folklore collections or her autobiography.

Robert E. Hemenway’s Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (1980) will also serve me well, in addition to Hurston’s own biography, as it examines the general reception of Hurston’s work during the Harlem Renaissance, reactions to Hurston herself, looks into influences on her writing style. For example, the chapter entitled “Ambiguities of Self, Politics of Race” discusses personal experiences like her brief and failed second marriage to Albert Prince III, who Hurston would later use as a type-and-shadow for Janie’s third husband in Their Eyes Were Watching God, Tea Cake. It also provides interesting insight into Hurston’s mid-life and late career, especially into her own doubts and depressions about the results of her life and writing career.

I am also using chapters out of The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (1989). This work benefits my thesis because of its address on the idea of signification in African-American literature: “It presents a number of illustrative examples of Signifyin(g) in its several forms, then concludes by outlining selective examples of black intertextual relations” (Gates 98). As of now, I’m not certain how intertextuality will surface in my thesis, if at all, but for the sake of responsible scholarship, I think it bears looking into at least. This text also looks at Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God as a speakerly text and addresses literary devices Hurston used to narrate her novel.

Along with scholarship specific to Hurston and her work, I intend to look at a couple of theorists who were largely influential to the idea of the Self and the Other, since it plays a significant role in my thesis. I will look at Jacques Lacan’s work on the mirror stage, specifically using the chapters “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience” and “On the Subject Who Is Finally in Question” out of the collection Ecrits: the first complete edition in English (2006). In simple terms, Lacan’s work suggests that the mirror stage is when children recognise themselves in relation to others for the first time, and it is at this point that they form an “I”–a sense of themselves as the Self or Subject.

Of course, I would be remise to address a gendered Self and Other without looking a feminist theory, so I will also rely on excerpts from Hélène Cixous’ “The Newly Born Woman” and her essay “Sorties” out of The Hélène Cixous Reader, edited by Susan Sellers (1994). In this ground breaking essay, Cixous used binary language to juxtapose terms such as Activity/Passivity, Culture/Nature, and Man set over Nature. These language binaries play into Cixous’ idea of l’ecriture feminine (feminine writing) and in her idea of the ways out of male centric authorship. Her essay will feature largely as I discuss Hurston’s use of binary images to create a Self and Other in Their Eyes Were Watching God and to also examine her narrative techniques.

Beyond these print sources, I will use online databases, such as Academic Search Complete and JSTOR to access scholarly journals, articles, and other materials that I may need during the months I work on my thesis. Also, as I included in a previous blog post, there is a film documentary on Hurston by PBS which I may look into as supplementary research and to engage in a different medium of scholarship around this amazing author.